Tuesday, July 17, 2018

The Rough Guide to World Music: Portugal

By Isabel de Lucena , Andrew Cronshaw

Portugal is best known as the home of fado, the passionate and elegant music of Lisbon and Coimbra

Amália Rodrigues (Augusto Cabrita)

Note that this Rough Guide to World Music article has not been updated since it was originally published. To keep up-to-date with the best new music from around the world, subscribe to Songlines magazine.

Portugal is best known as the home of fado, the passionate and elegant music of Lisbon and Coimbra. However, in its regions, a rich variety of traditional styles and instruments are still to be encountered, at family or civic celebrations or in concert performance. The “intervention song” movement articulated the mood for political change before, during and after the demise of the fascist dictatorship in 1974. As the country moves away from that turning point, alongside the development of Portuguese variants of global pop, rock, rap, electronic dance music and jazz, there has been a recent upsurge in the popularity of Lisbon fado. Isabel de Lucena and Andrew Cronshaw share out the custard tartlets between themselves…

Regional Traditions

Many of the strongest survivals of traditional music in Portugal are to be found in the rural areas away from the sea, such as Trás-os-Montes, Beira Alta, Beira Baixa and Alentejo, but each region has its distinctive living traditional forms with their characteristic ensembles and instruments.

In the northeast, Trás-os-Montes (behind the mountains) is a ravine-carved high plateau of burning summers and icy winters. It still retains not only the language of Mirandês, a relative of the old language of Spain’s León and Asturias, but also ways of making and hearing music which survive in few other regions of Europe. Neither the bagpipes found there (gaita-de-foles) nor the older of the traditional unaccompanied singers are enslaved by the mathematical equal-temperament scale of equal semitones which, largely because of the needs of Western classical harmony, has come to dominate the musics of the world.

The gaita-de-foles is closely related to the gaita of Spain’s Galicia to the north, with some similar tunes, and several dances, such as the murinheira (milkmaid), found in varying forms on both sides of the border. There are also links with Zamora to the east – for example, the dança dos paulitos, a men’s stick dance, which, like several dances in other parts of Iberia, is strongly reminiscent of an English morris-dance. Such dances are typically played by a gaita accompanied by a bombo (bass drum) and caixa (snare drum), or alternatively by a solo musician (tamborileiro) playing a three-hole whistle (flauta pastoril) with one hand and a small snare drum (tamboril) with the other.

In Minho and other parts of the north and west, the most common instrumental groupings, playing for dancing and celebrations, are the Zé-Pereiras, combining the caixa and bombo with wind instruments, and the rusga, which features assorted stringed instruments and percussion, often plus accordion, wind and reed instruments.

In Beira Alta and Beira Baixa, the central inland areas to the south of Trás-os-Montes, a key tradition is women singing in groups, in Beira Alta unaccompanied but in Beira Baixa self-accompanied on the adufe (a square frame-drum). Portuguese tradition is rich with songs for all aspects of day-to-day, festive and ritual life, and some draw on the oral ballad repertoire that was once widespread across Europe with stories dating back to the Middle Ages. Iberia has its own specific group of ballads, the Romanceiro, which were sung in the royal courts from the fifteenth until the seventeenth century, but continued in use in the fields and villages long after that, and in some cases up to the present day. Certain ballads were associated with specific canonical hours, giving fixed points dividing up the reapers’ long back-breaking days. A great many songs reflect the cycles of nature – lullabies, and tilling, sowing and harvesting songs. Until the 1970s they remained very much within living tradition, but while some survive, sadly, many now exist only in recordings or in the repertoire of revival and progressive folk bands which, however excellent, inevitably present the songs in a different context.

In the south, particularly Alentejo, there is a tradition of acapella polyphonic vocal groups, a vibrant Mediterranean sound comparable to that of the vocal ensembles of Corsica and Sardinia. In the Alentejo vocal groups, which are generally single-sex, a solo singer (the ponto) delivers the first couple of verses, setting the song and pitch, then a second singer (the alto) takes over the theme, usually singing it a third above the ponto’s preamble. After one or two notes he is joined, in the ponto’s pitch, by the full chorus, over which the alto sings an ornamented harmony line. As the song (moda) proceeds, the powerful group vocal alternates with expressive solo verses from the alto and sometimes the ponto. Essentially, this is spontaneous rather than chorally directed music-making, but there exist named performing ensembles, and it is these that are featured on most of the available recordings. They may be organized to a degree, but they’re not professional show-biz entertainers, they’re the real thing.

Quite a number of villages and towns have folklore ensembles known as ranchos folclóricos, who perform at festive occasions and sometimes on concert stages. These were encouraged by the dictatorship as exemplars of the happy colourful peasantry, and were therefore somewhat disapproved of by musicians who were opponents of the regime, but shedding those negative associations such ensembles continue to exist.

Fado

Fado is one of the most important European urban musical traditions and has, since the 1990s, become increasingly well established in the international music arena. This reflects the very healthy condition that this old genre currently enjoys at home in Portugal, where over the past few years it has re-entered the national music scene with a vengeance. Decades of stagnation caused by the influence of the fascist regime that dominated Portugal from 1926 to 1974 are now history, and a fresh generation of singers are now embracing the genre with renewed energy and passion.

Origins

The Portuguese word fado, which comes from the Latin fatum, translates as fate or destiny. But the meaning invested in this small word by the Portuguese is rich, deep and complex. It is their most representative traditional song, a symbol of national identity. Outside Portugal, it is the most melancholic side of fado that dominates the collective understanding of the style. Yet fado is a very diverse genre that can be either mournful or cheerful and is sung by men and women alike. This diversity is a clear legacy of its complex roots, which draw on a variety of cultures and styles.

It is impossible to be precise about the origins of fado, although many have tried. Contrary to theories that the style is an ancient art form, fado has been around for no longer than two hundred years, having emerged in the old city of Lisbon in the early nineteenth century. Probable influences on fado include African sensual dances such as the lundum and fofa and the Portuguese ballad form modinha, as well as Portuguese folk traditions and art music. It is, no doubt, an outcome of the constant interchange of cultural products between Africa, Brazil and Portugal, and the oldest documents that mention fado refer to the combination of music, lyrics and dance performed in the streets of colonial Brazil.

It was in the cosmopolitan working-class quarters of Lisbon, notably Alfama and Mouraria (both frequently referred to in fado lyrics), that fado first emerged in Portugal and, for a while, it was confined to the districts’ bars and brothels. Fado became the favourite entertainment of the lower classes that populated this district, a crowd composed of sailors, smugglers, recently freed slaves, rural migrants, thieves, black marketeers, prostitutes and other colourful characters, including bohemian elements of the aristocracy and students. Over the following decades, the genre developed stylistically as it expanded geographically and socially across Lisbon. Having absorbed traits belonging to several Portuguese popular traditions, courtesy of the rural folk who had by then settled in the capital, fado entered the salons of Portuguese high society via aficionados among the bohemian aristocracy. It was around that point that fado adopted the guitarra (Portuguese guitar) as its instrument of choice. Unlike the classical guitar, which was previously fado’s main accompanying instrument, the guitarra could produce a vibrato, which greatly emphasized and complemented the moaning of the voice, a prime characteristic of the style. The typical fado combo became a trio composed of guitarra, Spanish guitar and bass.

During its first century, fado underwent a continuous metamorphosis, dropping some of its initial traits while acquiring others, but by the time of the first recordings, at the very beginning of the twentieth century, it had already adopted the identifiable set of characteristics of the fado we know today.

Repression and relocation

At the beginning of the twentieth century, fado’s popularity was such that it could be heard in venues right across Lisbon. The elite enjoyed fado in the privacy of their salons, while the lower classes could hear fado in the new working men’s clubs and local associations, as well as at religious celebrations. Bullfighting was by then a hugely popular entertainment in which all sections of the population mixed without the usual class barriers, and fado was often performed at fights. Finally, fado could be heard in the retiros – inns along the routes into Lisbon which served the rural folk who constantly came in and out of the city in order to supply it with fresh food.

The middle class and bourgeoisie were the last to embrace fado, but in the early 1900s they caught up with the trend and were soon enjoying its performances, first in the theatre and later in cafés and brasseries. But the new political regime that took over Portugal in 1926 soon changed the whole scenario and, as early as 1927, new laws emerged restricting the performance of fado. Both artists and venues now had to hold performing licenses, and lyrics had to be officially approved before they could be sung. Most venues understood the implications of such laws and simply gave up on holding fado performances. But the great demand for the genre led to the emergence of fado houses – venues designed specifically for the purpose, which combined fado singing with food and drink, offering a great night out to the bohemians who could afford it, mainly the bourgeoisie. The fado houses tried to reproduce the decor of the old bars, but did so in an exaggerated manner, with all sorts of fado – and often bullfighting – paraphernalia hanging from the walls. Nevertheless, they became the genre’s sanctuaries, implementing a code of conduct based on great respect for song and singer, manifested by absolute silence, no service and low lights during the performance.

The emergence of the fado house had a great impact on the development of fado. On the one hand, singers became professionals with regular venues and an established network of contacts; on the other, doors were closed to those who were not part of that set. A two-tier fado scene emerged in Lisbon – that of the established names who had regular slots at the fado houses and were given record deals, and a grass-roots scene in which the non-professionals, including most newcomers, catered for an audience that could not afford luxuries. The alternative circuit, based mainly in the local clubs and associations, was continually breaking the law as neither venues nor singers held the licenses required and lyrics were not likely to be submitted for approval. It was here that the practice of desgarrada (an improvised clash between singers) was kept alive, as the law would not allow lyrics spontaneously made up on the spot. The clubs were also a breeding ground for new talent, and many stars began here before breaking into the professional scene.

Fadistas

In fado, the singer’s performance is of capital importance. The number of fado tunes is quite limited so all the originality lies in the singer’s interpretation of those tunes, and in their choice of lyrics. This explains why from fado’s very early days its greatest singers have become legends.

Maria Severa (1820–46) is generally considered to be the first great fado singer, or fadista. According to legend she was a prostitute from the Mouraria district of Lisbon and one of those responsible for introducing fado to the upper classes, through her love affair with the Conde do Vimioso, a bohemian count with a passion for bulls and fado, who was himself an accomplished guitarist.

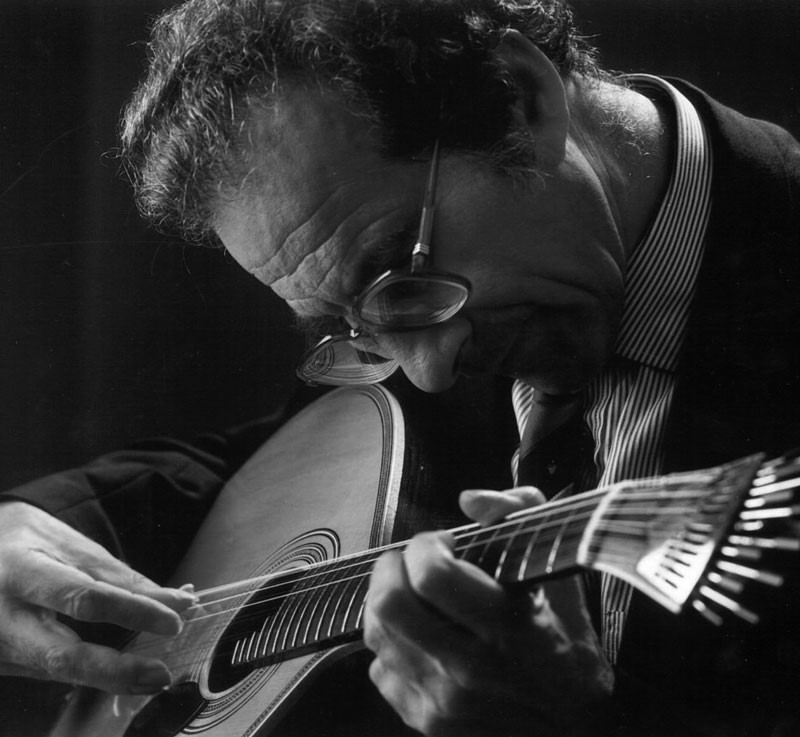

Performing fado involves being able to pour out pure raw emotion in a very particular manner. This requires a certain maturity and, even though a number of fadistas start singing at a very young age and some do it brilliantly, many maintain that suffering is a compulsory rite of passage to becoming a good fado singer. Fado singing is very much about personality, and being a good fadista is more about having a certain attitude and posture than about the quality of the singing voice. The great Alfredo Marceneiro (1891–1982) had a very rough and somewhat weak voice, yet he was the king of fado and a defining figure for the genre. His performances focused on the words rather than the music and he was a master of the use of pauses and intensity to make the music his own.

Alfredo Marceneiro

Purists still tend to react with outrage to any deviance from what they consider to be the norm, but most of the experimentation that is going on at the beginning of the twenty-first century is hardly any more radical than that undertaken decades ago by fadistas who are now revered figures. The 1960s and 70s were a period particularly rich in experimentation. Paradoxically, those were precisely the days when fado lost its appeal for the younger generations. In the 1960s, the Portuguese youth were far more interested in keeping up with foreign models of modernity, from the Swinging Sixties to May 1968, and in the 1970s their imaginations were captured by the revolution and associated artistic movements.

The queen of fado, Amália Rodrigues, who had observed the rules of fado for three decades, set out in a completely different direction the moment she teamed up with composer Alain Oulman in 1962. Her choice of poetry, melodies and accompaniment caused great outrage at the time. Then Carlos do Carmo arrived. The son of fado singer Lucília do Carmo, he was expected to follow her traditional style, but dived into modernity almost immediately. Having grown up on a diet of bossa nova, Brel, Sinatra and the Beatles, Carmo blended all those influences with fado to create a unique style that became extremely popular and greatly influenced the new generation of male singers. His performances were similarly modern: proper showbiz concerts, not necessarily in traditional fado venues, with all the requisite lighting, sound, wardrobe and so on. He also jettisoned the traditional guitar trio in favour of an orchestral accompaniment. Carmo championed fado canção like no other male singer before him. This sub-genre is closer to standard song in terms of melody and instrumentation, and takes a chorus-verse-chorus structure. It works well on radio and had been popularized through a particular type of Portuguese satirical theatre called revista. Carmo’s voice suited it perfectly and he made it very popular.

Amália Rodrigues

Amália Rodrigues’ death in October 1999 was marked in Portugal with three days of national mourning and her remains rest at the Panteão Nacional, a place reserved for national heroes. Internationally, she is still the best-known fado singer of all time, despite the great successes that have emerged from Portugal over the past few years.

Amália’s humble beginnings didn’t offer great potential. Born in 1920 into a large family, she was brought up in Lisbon, left school early and became first a seamstress and later a fruit seller. The idea of singing professionally was initially met with great resistance by her family but, championed by the great guitarist Armandinho (a friend of her brother’s), she eventually started performing at the prestigious Retiro da Severa.

Her taste for erudite poetry and her original singing style, reminiscent of Arabic chants, resulted in a sophisticated product, and she soon became the elite’s favourite entertainer, gaining access to a world not available to other singers. By the early 1940s, she had already achieved a very privileged position.

Over the following four decades, Amália spread the fado gospel and a taste of Portugal across the globe, first in countries culturally close to Portugal such as Spain and Brazil, and later throughout the rest of Western Europe, Africa, the US, the Middle East, Australia, Japan and the Soviet Union.

Amália had the voice, looks, charisma and connections that allowed her to become a great international success, but her importance goes far beyond acting as an ambassador for both fado and Portugal. Her great legacy is the input she had on fado as a style – re-shaping it by bringing modernity into it, turning it into a contemporary art form. This happened after she teamed up with Alain oulman, the Portuguese-born composer of French/Jewish descent with whom she established a working relationship from 1962 onwards. Together they challenged norms and pushed boundaries by (controversially at first) creating fados from poems by the great sixteenth-century poet Luis de Camões as well as contemporary writers, leaving fado a different genre to the one they first encountered. Their legacy lives on and couldn’t be healthier than in the hands of the prolific new fado generation.

The new fado scene

When Amália died in October 1999 no significant new fado stars had emerged on the scene for some time, and, with the loss of its queen, the future of fado seemed seriously threatened. An obsessive search for her successor ensued. Miraculously, this quest for a voice to fill the void seemed somehow to trigger a fado revival. Certainly, it coincided with the emergence of a new generation of fado performers who have reinvigorated the genre and brought it triumphantly into the twenty-first century.

It was at a 1999 “Tribute to Amália” concert that the present figurehead emerged. Mariza had started singing fado during childhood, in her parents’ restaurant in the Lisbon neighbourhood of Mouraria. After a break during which she concentrated on more modern genres, she returned to fado towards the end of the 1990s, and the timing couldn’t have been more right. She had a great impact, and the obvious comparisons to Amália were soon made. Such comparisons were quite common at the time, but the Mariza fad never went away and her subsequent international success suggests she truly is the heir to the fado throne.

Mariza (Isobel Pinto)

Particularly at home, Amália shared the limelight with contemporaries including Hermínia Silva (1913–93) and Maria Teresa de Noronha (1918–93). Similarly, Mariza is just one among many talented new voices that have emerged almost simultaneously over the past few years. This new fado boom seems unreal, particularly considering the lack of interest by consecutive generations in the past. But there are several factors at stake – mainly the coming of age of a generation born around or after the revolution, whose feelings towards fado are not tainted by any memories associating the genre with the dictatorial regime. There has also been a notable change of attitude towards cultural identity, which can be seen as a reaction against globalization. Finally, despite appearances, the new fado has not come out of the blue, but is the result of a gradual build-up. Since the early 1980s a number of young and sophisticated artists had been flirting with fado, incorporating its traits into their looks, posture and sound. By fragmenting the genre and using its elements on a pick-and-mix basis, these artists presented a much lighter and constraint-free view of fado, which must have looked quite appealing to the young who in previous decades tended to think of it as too dated, too serious and too distant from their reality.

The first of these artists was António Variações (1944–84). His first single, out in 1982, was a version of Amália’s “Povo Que Lavas no Rio”. With his fado-infused pop, Variações managed to appeal to a wide audience, from mainstream fado lovers to members of the most alternative tribes. The new romantic trend, so popular in the early 1980s, made Variações and his music look bang up-todate and his celebration of national identity was in tune with the work of other successful Portuguese acts of that time, in particular Heróis do Mar. This Portuguese band reached unprecedented levels of international credibility in the 1980s and, having toured with Roxy Music and been voted Best European Band by youth culture bible The Face, their judgements and alliances were relied upon at home. They produced Variações’ second album, Dar e Receber, which was released shortly before his premature death in 1984.

Madredeus were very successful in the late 1980s, both in Portugal and around the globe, and are still a substantial draw today. With singer Teresa Salgueiro, they introduced a fado-inflected style of popular Portuguese music to the world. Emerging in the early 1990s, Mísia was arguably the first singer of what became known as the “new fado”, despite the fact that her sophisticated approach has always been better appreciated abroad than at home. Singer Dulce Pontes started by representing Portugal at the 1991 Eurovision Song Contest, and is now internationally renowned for her collaborations with Ennio Morricone. She has maintained an on-off relationship with fado, and Amália’s beautiful “Canção do Mar” reached a world audience when Pontes’ version of it was included in the soundtrack of the Hollywood film Primal Fear. Paulo Bragança enjoyed some international attention in the mid-1990s when he recorded for David Byrne’s label Luaka Bop.

The international recognition of these artists prepared foreign audiences for fado and simultaneously made the Portuguese more confident about and appreciative of their national genre. But even though fado currently enjoys great popularity in Portugal, its revival has been met with immense caution by the Portuguese record industry, and many artists, including Mariza, were first signed by foreign rather than Portuguese labels.

Aside from Mariza, many other female fado singers have been leaving their mark both at home and abroad. Cristina Branco keeps swinging between styles, but the fado chemistry that results from the combination of her vocals with Custódio Castelo’s guitar playing is undeniable. Katia Guerreiro’s Amália-style singing is the favourite among the most nostalgic aficionados. Ana Sofia Varela infuses her fado with influences from her native Alentejo and from Spanish music. And there are a number of other voices, such as Mafalda Arnauth, Ana Moura and Joana Amendoeira, who have been around for a while and consistently offer very high-quality fado.

Because of memories of Amália, it is much easier for female singers to be accepted in the international arena, but new fado also includes a number of extraordinary male voices. Camané won the most prestigious Portuguese fado contest, the Grande Noite do Fado, in 1979 at the age of twelve and, after a break of a few years, matured into a great success both live and on record. Camané comes from a family of fado aficionados and his two brothers Pedro and Helder Moutinho have also been making waves in the new fado scene. Other male voices of this young generation include António Zambujo, whose fado is tinted with sonorities of Alentejo’s typical singing style cante, and Gonçalo Salgueiro.

While a great number of artists have embraced pure fado, there are others who still prefer to flirt with the genre from a distance, for example Ovelha Negra, A Naifa, Chillfado and the singer Lula Pena. The blind triangle player and former street singer Dona Rosa, who has received surprisingly wide exposure outside Portugal in recent years, is often misidentified abroad as a fado singer, partly because of the sad poise of her singing, but in terms of material she’s really a singer of folk songs.

Coimbra Fado

There is another side to the fado story – the fado of Coimbra. It was the migrant student population that introduced fado to Coimbra in the mid-nineteenth century. In those days, the university city attracted the vast majority of Portuguese-speaking students. Every year newcomers arrived from as far away as Brazil. This almost exclusively male student population came from a privileged background and often brought with them new trends that would become popular amongst fellow-students.

Soon after making its debut in Coimbra, fado began to change. Lisbon fado was a product of a very particular set of influences; it was the voice of the lower classes and the defeated. Even though that had a certain appeal to the bohemian student population of Coimbra, who embraced it without hesitation, it didn’t speak for them, and when they produced their own fado, the result was naturally different. The majority of Coimbra singers and players were young, male, highly educated and, far from having lost hope in life, were starting it from a privileged position. And so, little by little, with new compositions, fado moved away from its origins.

A comparison between the first legend of Lisbon fado and her Coimbra counterpart is sufficient to illustrate the difference between the two branches of the style. Whereas Maria Severa was a prostitute from one of the poorest districts of Lisbon, Hilário (1864–96) was a medical student and a celebrated poet. Hilário excelled at the romantic, four-stanza songs typical of the Coimbra style, which, inspired by the international romantic trends popular amongst the students, became a serenade with melodic and harmonic characteristics very different from Lisbon fado. Many assert that “Coimbra serenade” or “Coimbra song” would better describe the style than “Coimbra fado”, which implies it is just a sub-genre or branch of Lisbon fado.

Coimbra fado had its heyday in the 1920s, with the emergence of a number of singers and musicians that became known as Coimbra’s Golden Generation. Singers such as António Menano, Edmundo Bettencourt, Lucas Junot and José Paradela de Oliveira and the guitarist Artur Paredes refined and solidified the template laid down by Hilário and her contemporaries.

Artur Paredes adapted the Portuguese guitar, creating a new version of the instrument specifically designed for playing the Coimbra style. He also developed a number of new techniques, and attracted numerous followers and imitators. The Paredes dynasty of guitarists that had begun with his father and uncle Gonçalo and Manuel Paredes reached its highest point with Artur’s son Carlos Paredes (1925–2004), the greatest exponent of the Portuguese guitar so far, but an artist who early on departed from fado, surpassing it and creating a unique style. Today António Chainho is the leading soloist on Portuguese guitar, while the brilliant Pedro Caldeira Cabral draws on the Coimbra fado repertoire and has explored guitarra repertoire going back to the sixteenth century.

Carlos Paredes (Casa Do Fado E Da Guitarra Portuguesa)

During the 1950s and 60s there was another wave of excellent Coimbra fado singers. Yet some of these felt the need to detach themselves from the genre, as the gap between their left-wing student ideology and what Coimbra fado had to offer as an art form proved too wide to bridge. António Bernardino is the most representative figure of this generation. He toured extensively and saw his records released around the globe, enjoying an international popularity previously unrivalled in Coimbra fado.

Coimbra fado has recovered from the bad press it received in the 1960s and 70s and currently enjoys fairly good health and popularity among the students. The presence of some singers and guitar players among the teaching population of the university is enough to keep the tradition alive and every year a number of new students join the group. Even so, Coimbra fado is not enjoying anything like the renaissance of Lisbon fado. It can be heard regularly at the end of the academic year celebrations and at Bar Deligência in Travessa da Rua Nova, but not at an ever-growing multitude of places like its Lisbon counterpart. Unlike Lisbon fado, Coimbra fado does not seem alive and evolving, but rather crystallized in time.

Intervention Song and Roots Groups

In the second half of the twentieth century, and particularly in the years following the revolution of 1974, a new style emerged in Portugal, cancão de intervenção (intervention song). Shaped by a wide variety of influences ranging from Portuguese traditional styles (including fado) to Brazilian music, French song, rock and jazz, this new style bore similarities to the Latin American nueva canción (new song). In addition, from the 1970s onwards, groups have emerged in Portugal re-exploring regional traditions and often fusing them with rock and jazz influences.

José afonso and Intervention Song

The great figure of twentieth-century Portuguese popular music was José Afonso (1929–87). Born in Aveiro, he spent part of his youth in the Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique, where his father had placements as a judge. Afonso later entered Coimbra University where he started singing fado. His first recordings were of Coimbra fado, but in the 1960s, he began to distance himself from the style, which did not have enough strength as a political tool to fight the dictatorial regime. He and his contemporary Adriano Correia de Oliveira became pioneers of the Portuguese protest song movement. In the years running up to the 1974 revolution, Afonso was the leading figure in the reinstitution of the ballad – in the sense of a set of artistic, poetic, usually contemporary lyrics set to music.

In the final years of the dictatorship, censorship and the restriction of performing opportunities caused some songwriters to move abroad and record there. But Afonso remained, where necessary masking social and political messages with allegory, and having to combine professional and family life with censorship and imprisonment. His songs were both rallying points for those who longed for the emergence of a democratized state and standard-bearers for a new Portuguese music.

One of Afonso’s songs, which oddly enough hadn’t been banned by the censors, became synonymous with the Portuguese revolution: “Grândola Vila Morena” was selected by the Captains of April (the group of rebel army officers who masterminded the Portuguese revolution) as the cryptic go-ahead signal for the military coup that put an end to 48 years of fascism. A national radio station played the song at 25 minutes past midnight on 25 April 1974, so troops all over the country knew that the time had come for action.

Afonso and Adriano Correia de Oliveira were joined in the protest song movement by singersongwriters Luis Cília, José Mário Branco, Sérgio Godinho and others. But after 1974 there was a need for songwriters to move from protesting under oppression to exploring the needs and possibilities of the new democracy; protest song evolved into intervention song and other related sub-movements. In shaping the new forms, songwriters drew on influences both within and outside Portugal.

Sérgio Godinho, who was born in Oporto in 1945, opted to go into exile when faced with joining the army and fighting in the colonial war. He left Portugal aged twenty, returning only after the revolution had taken place, having lived in Paris, Amsterdam, Vancouver and Brazil, thus becoming exposed to a great diversity of influences. He recorded his first two albums in exile. An outstanding lyricist, he is one of the most important Portuguese singer-songwriters and a very prolific one too. He is also an actor, writer and director. A number of his albums have become classics, among them Coincidências, which came out in 1983 and features collaborations with some of the most important names in Brazilian popular music – Chico Buarque, Ivan Lins and Milton Nascimento. Godinho is still going strong in the twenty-first century.

Vitorino’s lyrics and particularly his titles often have a surreal tinge, suggesting the work of such South American writers as Gabriel García Márquez, but his music is strongly linked with the traditions of his native Alentejo. His brother Janita Salomé brings in the Arab influence of the south of Portugal. Both are well known as solo artists, and for performances with José Afonso. Together they have performed intermittently with the group Lua Extravagante, with Alentejo vocal group Cantadores do Redondo and with Vozes do Sul.

Fausto’s first album appeared in 1970, and he has gone on to become a major songwriting force, combining traditional forms and instrumentation with a rock sensibility. His albums feature many other leading musicians including Júlio Pereira, who began as a songwriter, played with José Afonso, and has become a fount of knowledge and skill on traditional Portuguese stringed instruments. Even though they are often not thought of as part of the movement, because they are instrumentalists rather than singers, musicians like Júlio Pereira and Carlos Paredes are figures of great relevance to the intervention song scene.

Younger singers and songwriters, such as Amélia Muge, continue to draw on a mixture of rural and fado traditions, and you’ll frequently hear songs by Afonso, Godinho and other intervention song leaders in the repertoire of the new fado singers. Singer Né Ladeiras, formerly a member of the group Brigada Víctor Jara, went solo in 1983 and has made a string of notable pop and roots albums since then, including one devoted to Trás-os-Montes music and another featuring the songs of Fausto (one of her strongest influences), drawing them closer to traditional instrumentation and feel.

Roots Groups

It isn’t just individual songwriters who have been drawing on Portuguese traditional music. In the 1970s groups began to form that devoted their attention either to the research and performance of traditional music from one or more regions, or to the construction of new music with folk roots. While sometimes such work is viewed as a quest for a lost ruralism, in a newly democratized state it is often an important part of self-rediscovery.

Portugal’s rich rural musical traditions were, and to varying extents still are, alive and functioning, so the gathering of material involved a trip not to dusty archives but to the villages. Ranchos folclóricos might have had the residual scent of dictatorship approval, but the new groups were closer to the spirit of intervention song, and their members often appeared on the recordings and in the bands of the singer-songwriters.

This socially aware connection is seen most obviously in the name of the pivotal roots-with-evolution group Brigada Víctor Jara, formed in Coimbra in 1975. Today it contains no original members, but continues to be a major force, and former members have gone on to create new projects. In finding material, the band collaborated with a man who did a huge amount to document traditional music and make it available to listeners, ethnomusicologist Michel Giacometti. Together with Fernando Lopes Graça, this Corsican-born Frenchman made a large number of field recordings throughout Portugal, which were released on various labels from the 1950s onwards.

Brigada Victor Jara (fRoots Archive)

Some bands, such as Brigada Víctor Jara, have been a fairly steady presence on the Portuguese music scene, while others have waxed and waned, almost disappearing from view and then returning with a new line-up or new album. Notable names over the years include Raízes, Ronda dos Quatro Caminhos, Trigo Limpo, Terra a Terra, Trovante, Grupo Cantadores do Redondo, Almanaque, Romanças and Toque de Caixa.

Leading traditional groups including Brigada Víctor Jara, Vai de Roda and Realejo have all moved on to a more detailed exploration of sound and the possibilities for development than that which prevailed in the first wave. A powerful and innovative more recent arrival is Gaiteiros de Lisboa, which combines gaitas and other wind instruments with drums and Alentejo-style vocals. Bypassing the Western tradition of chordal music, they have created a modern context for the much older layer of music that’s still to be heard in Trás-os-Montes and elsewhere, governed not by harmony but by rhythm and melody, free from the rigidity of the equal-temperament scale.

The diatonic accordion quartet Danças Ocultas explore new compositions for this versatile instrument. Although the instrument is widespread in Europe, there are distinct playing styles associated with it in some regions of Portugal, where it is known as a concertina. The group draws music not just from the reeds of the instrument, but also from less obvious sources such as the panting of the bellows.

At-Tambur’s music fuses Portuguese and foreign traditions. Classical and jazz influences are visible in their arrangements of both their own creations and traditional music, which use concertina, violin, flute and accordion side by side with double bass, guitar and a drum-kit. The group’s very comprehensive website (www.attambur.com) is an excellent source of information about Portuguese traditional music and musicians.

In Trás-os-Montes, the old tradition of gaitade-foles (bagpipes) just survives, principally in the easternmost tip, Miranda do Douro, hard up against the Spanish border. Of the handful of traditional gaiteiros remaining there, two of the best are in the quartet Galandum Galundaina. This group of fine musicians and singers play their region’s traditional instrumental combination of gaita (and occasionally flauta pastoril), bombo (bass drum) and caixa (side drum) as performance and also to accompany the pauliteiros (male stick-dancers).

Over the past few years, all-female vocal ensembles have also appeared on the Portuguese new roots scene. Among them are Moçoilas, who concentrate on reviving the singing tradition of the Algarve, and Segue-me à Capela, an interesting group which researches traditional music from all over the country and interprets it in arrangements centred around the voice, sporadically using percussion instruments.

Groups performing rural folk music continue to emerge and make CDs. Among them are Sons Do Vagar, Isabel Bilou and Susana Russo, who sing, in the traditional way, songs collected in their native Alentejo, largely in attractively empathic duet, either acapella or, on their CD, simply accompanied by the rural guitar viola campaniça with interludes of other Alentejo instruments including the friction drum sarronça, diatonic accordion, flutes and percussion. Toques do Caramulo is a skilful and assured band from Águeda in west central Portugal led by singer, accordionist and braguesa player Luís Fernandes with fiddle, mandolin, flute, guitar, bass and traditional percussion doing lively, creative arrangements of traditional songs from the local Caramulo mountains.

Portuguese instruments

Strings

The guitarra, with its delicate, silvery sound, is the principal instrument used in fado, to accompany a singer and also to play the lead in instrumental groups. Though known as the Portuguese guitar, its body isn’t guitar- shaped but more like a fat tear-drop in outline. It’s a variety of the European cittern, which arrived in Portugal in the eighteenth century in the form of the “English guitar” via the English community in Porto, where it was used in a style of art-song ballad known as modinha which was popular at that time in Portugal and Brazil.

There are two types – the Lisboa guitarra used for accompanying singers, and the Coimbra version, with a larger body and richer bass more suited to that city’s instrumental fado. Both have six pairs of steel strings tuned by knurled turn-screws on a fan-shaped machine head. The bottom three pairs have one string an octave lower than the other, giving a chiming resonant bass supporting the silvery singing vibrato and fluid runs of the unison-tuned top three pairs.

In fado, the guitarra is usually accompanied by a viola de fado, a six-string guitar of the familiar Spanish classical form but which, like all fretted instruments of that waisted body-shape, is known in Portugal as a viola. A remarkable range of other specifically Portuguese violas are found in regions of the mainland and islands. Varying in shape, they’re virtually always steel-strung, and some have soundboards decorated with flowing tendril-like dark wood inlays spreading from the bridge, and soundholes in a variety of shapes.

The version encountered most often, particularly in the north, is the viola braguesa, which has five pairs of strings and is usually played rasgado (a fast, intricate rolling strum with an opening hand). A slightly smaller close relative, from the region of Amarante, is the viola amarantina, whose soundhole is usually in the form of two hearts; a similar soundhole pattern is found on the viola da terra of the Azores.

Other varieties include Madeira’s slim viola d’arame, Alentejo’s bigger viola campaniça and Beira Baixa’s viola beiroa. The last of these is distinctive in having an extra two pairs of strings running from the bridge to machine heads fixed on the body where it meets the neck; these are used in a similar way to the high fifth string on an American banjo.

Like a baby viola with four strings, and played with an ingenious fast strum akin to the braguesa’s rasgado, the cavaquinho is not only widely played in its home country but has spread across the world, including to the biggest Portuguese-speaking country, Brazil. It has also reached Hawaii, where it has become, with very few changes, the ukulele.

The Portuguese form of mandolin, the bandolim, also has its role in tradition. A particularly fine player is Júlio Pereira, who is also an expert exponent of cavaquinho and the range of violas.

The sanfona (hurdy-gurdy) fell out of use in the early twentieth century but is now being built and used again by such groups as Realejo and Gaiteiros de Lisboa. The rabeca or ramaldeira of Amarante and Douro is a short-necked folk rebec, and in Madeira the one-stringed bexigoncelo functions as a bowed bass with a pig’s bladder as its soundbox.

Wind

The gaita-de-foles is the Portuguese bagpipe (the word fole means “bag”), played in Trás-os-Montes. Many European bagpipes use a scale different from modern equal temperament, and the gaita-de-foles diverges more than most; since it’s not played ensemble or with other pitched instruments but only with percussion, the scale of each gaita’s chanter is individual, tuned by ear and to the sung scale.

The flauta pastoril (three-hole whistle) and tamboril (tabor drum with snares) are played particularly in Trás-os-Montes and eastern Alentejo. The three-hole whistle is sometimes called pífaro, a term that also applies to a fife or whistle, an instrument found in several regional traditions. Other wind instruments used include accordion, concertina (diatonic accordion – what in English would be known as a melodeon, not the English concertina), ocarina and clarinet.

Percussion

The thump of Portuguese traditional music is created by bombo (bass drum), caixa (small side drum with gut snares), adufe (square double-headed drum, sometimes called pandeiro) and pandeireta (tambourine) or cântaro com abanho (a clay pot struck across its mouth with a leather or straw fan). In Alentejo there’s sometimes a grunt, too – that of the sarronça, a friction drum made from a clay pot with skin stretched over the mouth; rubbing a stick set into the skin produces the sound, as it does the sound of Brazil’s higher- pitched cuica.

The clatter comes from the jingles of the pandeireta and from a range of other devices including the clank- ing ferrinhos (triangle), conchas de Santiago (scallop shells rubbed together), castanholas (castañuelas, or in Madeira a chain of ten flat shell-shaped boards), cana (a split cane slap-stick), trancanholas (wooden “bones”), reco-reco or reque-reque (a scraped serrated stick) and zaclitracs (a form of rattle). Finally, there is the genebres, a wooden xylophone hung from the neck, which features in the dança dos homens (men’s dance) in Beira Baixa, and, lost from the mainland but still found in Madeira, the brinquinho, a cluster of wooden dolls each with a castanet on its back, mounted in circles on a pole.