Wednesday, May 8, 2024

Still Life: Celebrating 100 Years of Emahoy

Robin Denselow celebrates the remarkable Ethiopian nun and musician Emahoy Tsege-Mariam Gebru who would have been 100 on December 12

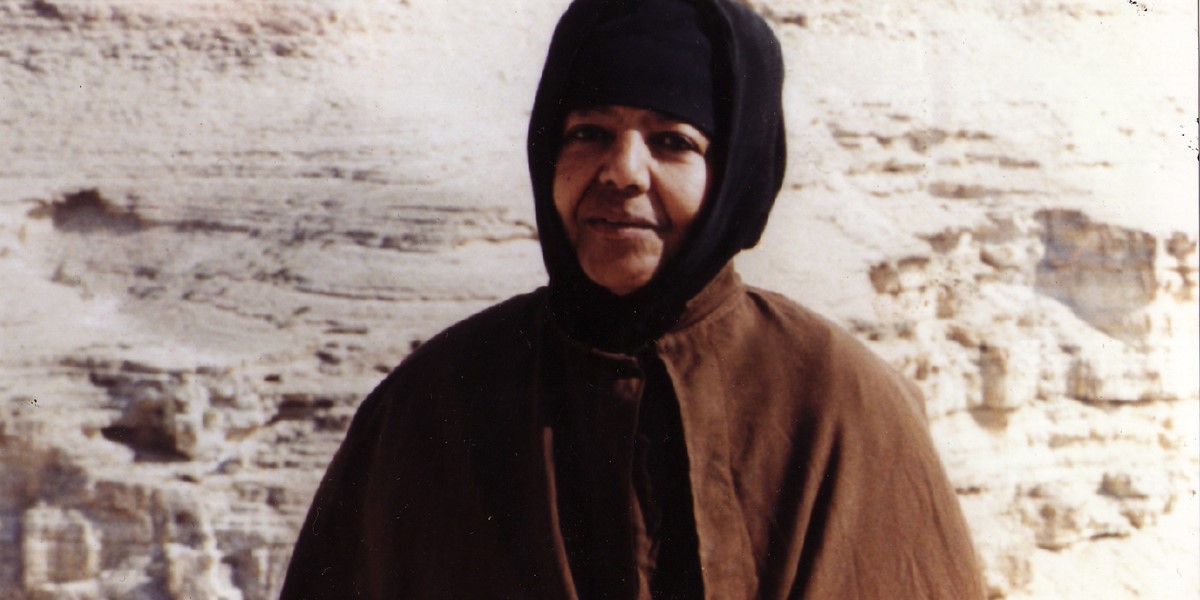

Emahoy Tsege-Mariam Gebru

Emahoy Tsege-Mariam Gebru, or simply Emahoy (using the religious honorific she was known by), played a unique role in the story of African music. A composer and pianist who died in March this year aged 99 (she would have turned 100 on December 12), she gave few concerts and recorded only a handful of studio albums, but created a compelling, intriguing fusion of different styles that include Western classical and Ethiopian church music. She was in her 80s when she first became well-known outside Ethiopia, and was then a nun, living in an Ethiopian Orthodox monastery in Jerusalem. Her breakthrough came with the compilation album The Very Best of Éthiopiques (2007), which included a front-cover endorsement from Elvis Costello, who enthused ‘Do yourself a favour and discover… soulful, sorrowful and joyful music.’ Emahoy certainly ticked all those boxes with her track ‘Mother’s Love’, though her music was utterly different to that of the other great musicians on the set, who ranged from Ethio-jazz legend Mulatu Astatke to Ethio-rocker Alèmayèhu Eshète.

The Éthiopiques series was the work of Francis Falceto, a French producer married to Emahoy’s niece Jappi Yilma, who had become fascinated by what he calls Ethiopia’s “golden age” of music back in the 60s and early 70s when Addis Ababa was “the African answer to swinging London.” This remarkable set of albums – which won Falceto the Songlines World Pioneer Award in 2017 – includes Éthiopiques, Vol 21: Piano Solo (2006), an album of pieces by Emahoy. Among the songs are the tuneful, charming and emotional ‘Ballad of the Spirits’, and the sensitive but sometimes playful ‘The Last Tears of a Deceased’ with its echoes of anything from Western classical to almost ragtime styles, and precise, delicate playing involving a sudden cascade of notes. And then there’s the blend of Western and Ethiopian religious influences in ‘The Jordan River Song’, or the conflicting moods of joy and sadness in the melodic ‘Homesickness’ and ‘Song of Abayi’.

For Falceto her work was “something deeply Ethiopian, in spite of her musical background. Her sense of melody is absolutely great, with few notes.” For those two qualities, he compared her to the French composer Erik Satie. For Thomas Feng, a pianist who is currently writing a dissertation on Emahoy for his PhD at Cornell University, New York, her work is “uniquely situated between so many musical and cultural worlds, and challenges us to rethink what those genres and worlds really are… she’s classical music, but not quite, though often compared to Chopin and Beethoven, and jazz musicians think of her as jazz-like, but different…”

It was indeed an extraordinary musical style, and the reflection of an extraordinary life. Born Yewubdar Gebru on December 12, 1923, she came from an important family – her father was a traveller, author and diplomat who Francis says “was one of the pioneers of Ethiopian intellectuals – his life deserves a book.” When she was just six years old she was sent away to study in Switzerland, where she first learned piano and violin, before returning to Addis four years later to continue her studies. She was not able to stay for long, as in 1936 Mussolini’s troops invaded the capital, and Yewubdar and other family members were deported to Italy.

After the war she was able to continue her musical studies in Cairo, this time under the tutelage of the Polish violinist Alexander Kontorowicz. According to her niece Yilma: “from her shorthand-written autobiography her happiest memories are in Cairo where she played piano for five hours and violin for four hours daily.” In 1944 she and Kontorowicz both travelled back to Addis, where Emperor Haile Selassie appointed him as musical director of the Imperial Body Guard Band – a key role at a time when many of the best singers and players worked for state-controlled bands.

Yewubdar had become a key figure in the Addis social scene, a multi-linguist and brilliant musician who had studied Bach and other Western classical composers, and was now writing her own compositions. But her glamorous life began to go wrong. According to another niece, Hanna Kebbede, “Kontorowicz never contacted her after she returned to Ethiopia, and that abandonment was part of the heartbreak regarding her musical ambitions.” She had hoped to move to England to continue her piano studies, but it’s believed the move was blocked by the Emperor himself. Why would he do that? There are many theories, and in the sleeve notes to Éthiopiques 21, Falceto suggests that one of Selassie’s sons had wanted to sponsor her, but the Emperor disapproved. So, what happened? “It’s difficult to speak about it. It’s delicate and private. You can read between the lines.” As for Kebbede, she replies “that’s not a question I’m going to answer. There are rumours and speculation surrounding her early life. There’s a documentary about Emahoy in production which has her own words on it – I’d prefer this question to be deferred to be answered at that time!”

Emahoy with her niece Hanna

Not being able to realise her artistic aspirations was a major upheaval in the young musician’s life. She was devastated,became ill, and gave up on Addis society, becoming a nun at the Gishen Mariam monastery in Wollo, in the Ethiopian highlands. Here she lived for a decade before returning to the capital because of ill health brought on by the harsh regime. According to Kebbede, she began teaching “at a school for the blind, where many were orphans,” and resumed her musical career, as a pianist and composer. In 1963 she travelled to Germany to make her first studio recordings, giving all the money she earned to the orphanage of the Armed Forces Wives Association, a charity founded by her sister Desta Gebru which provided support for widows and the children of soldiers who died during the war.

In 1967 she travelled to Jerusalem in the company of her mother, staying in the city for five years, working in the Ethiopian Orthodox monastery administration. On returning to Addis she continued to compose and play piano, sometimes recording her work on a cassette recorder. Yilma remembers, “she lived with her mother, our home was next door, and played piano in her room. Emahoy went back to Jerusalem [in 1985] after her mother’s passing.”

She spent the rest of her life living in a small abode near a monastery next to Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre. For many years she didn’t have access to a piano. As a nun, she had retreated from the world. She never wished to make money from her music, though she was clearly keen for it to be heard. In 1998 she contacted her niece Kebbede, then living in New York, asking for her help selling 300 copies of a CD she had self-published. Kebbede says she went to Jerusalem to visit Emahoy, who told her she was worried that “when I die my music sheets are going to be thrown out… please help me,” She says she returned with a suitcase “full of her music sheets and all her tapes… making me a steward of her work”.

While looking for a record label that would be interested in releasing Emahoy’s music in the West, Kebbede learned about Francis Falceto and his Éthiopiques project. Falceto had already heard of Emahoy because “she was a kind of legend… and some Ethiopians living in Paris had drawn my attention to her and gave me a vinyl recording. So, when the family asked me if I could do something, that was the best!” Kebbede sent him various recordings she had, and he searched out the rest: “I found them all,” he says. “I was a crazy researcher! In Ethiopia it was already the time of cassettes, people didn’t have turntables, but I found some copies in good condition in the back rooms of music shops, allowing us to make quite an honest restoration.”

Emahoy was delighted at the success of her Éthiopiques recordings. Falceto and Yilma visited her in the Jerusalem monastery (most recently, a month before her death) and found “she much enjoyed her late celebrity. She knew she was famous, and was fond of receiving young musicians and journalists. She had Facebook… and was very interested in what was going on in the artistic life, from Hollywood to Addis Ababa.” In 2008 she had travelled to the US, for a rare concert in Washington DC.

Since then, Emahoy’s reputation has continued to flourish. Her niece Kebbede created the Emahoy Tsege Mariam Music Foundation, to fund music education programmes for children from under-served communities, and this year, she says, “the Foundation funded 28 children for one-on-one piano lessons for a year and gave music scholarships to needy children at an Addis Ababa school where it purchased instruments to reactivate a music department.” Other projects have included summer camps in Israel and the US. A subsidiary organisation, Emahoy Tsege Mariam Music, can “commission work or make commercial transactions,” which include t-shirts and sweatshirts featuring the names of Emahoy’s compositions.

Emahoy may have become known through the exquisite recordings released through the Éthiopiques album, but this was just a fraction of her work. Along with the albums she recorded in Germany there are home cassettes of her compositions, and also sheet music, some of it for pieces she never recorded. The pianist Thomas Feng first heard her music “around 2018/19, when I was in New York around a lot of cool people – the hipster contingent of Emahoy’s fans.” He got in touch with the Foundation and has helped to digitise and catalogue the archives. Kebbede considers Thomas “an Emahoy aficionado, he performs her music beautifully,” and was invited to play at Emahoy’s funeral. While in Jerusalem he “found a lot of scores in her room,” which he has also helped catalogue. On November 7 he was one of the artists performing “pieces not widely heard before” at a concert ‘celebrating her musical legacy’ at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC.

The American label Mississippi Records has been reissuing Emahoy’s recordings since 2012, including a reissue of 1963’s Germany-released Spielt Eigene Kompositionen and a compilation bringing together many of the songs from Éthiopiques 21 on vinyl for the first time. This year the label released Jerusalem, which included songs from a 10” that Emahoy released in 1970, as well as pieces she recorded on cassette while still in Addis Ababa. Among these is ‘Quand la Mer Furieuse’, the first track on which she can be heard singing, accompanying herself on piano. Her first vocal album is set for release via Mississippi in early 2024. According to Kebbede there are “30-40 recordings not released, that will be issued in the future, and there are the music notes that other people can perform and record – songs she never recorded, but wrote music [for]. She also wrote for the violin, the organ, operettas…” Kebbede’s plan is to get them digitised, placed “somewhere like the Library of Congress, so it will be accessible to anybody doing research or interested.”

It’s an impressive archive, but what of the quality of these unreleased songs? Thomas Feng, who helped with the Mississippi compilations, says, “there’s a certain charm to the home recordings. A kind of intimacy.” With more material still to be released, and the film on her life now in post-production, this extraordinary Ethiopian nun has most certainly not been forgotten, on what would have been her 100th birthday.