Friday, December 6, 2019

Macha & Chico Trujillo: “In Chile, they have generated something very beautiful with the cumbia”

The Chilean musician known as Macha fronts a variety of ever- evolving bands, such as Chico Trujillo and Bloque Depresivo. Russ Slater chats to him about how it all began with cumbia

(photo: Camila Berrio)

Aldo Asenjo, known simply by his nickname Macha, does not claim to be a master of cumbia or bolero, but through his bands Chico Trujillo and Bloque Depresivo he has injected new life into those styles, revamping their status not just in his own country, Chile, but across the world. As recent audiences across Europe can attest, whether Macha is in festive mode with Chico Trujillo or ringing out the emotion with Bloque Depresivo, there is no way you can get through his shows without being moved (be that emotionally or physically).

It’s been quite the journey to get to this point. Macha grew up in Villa Alemana, a small city near Valparaíso on the Chilean coast. It was there that he formed his first band, La Floripondio, in 1991. Playing rock with a horn section and elements of ska and punk, they’re still active, although it’s fair to say they’ve been usurped in popularity by his other projects. Chico Trujillo was next in line, starting as an offshoot of his earlier group, with both the location of Germany and a love of cumbia playing an important role.

“When I was a kid I listened to what was played on the radio and to bands like Los Jaivas or cumbias that my uncle’s family listened to,” Macha tells me. “They liked cumbias and parties a lot, so there was always cumbia present.” As La Floripondio evolved they became more adventurous, and on a tour of Germany in 1998 Macha started playing acoustic guitar as the lead instrument for the first time. Soon they had written a handful of slower songs with a more ‘traditional’ flavour that didn’t really fit with what the group was doing. Chico Trujillo were born to play these songs, with a repertoire that soon included originals and covers of all those cumbias that Macha had listened to as a kid.

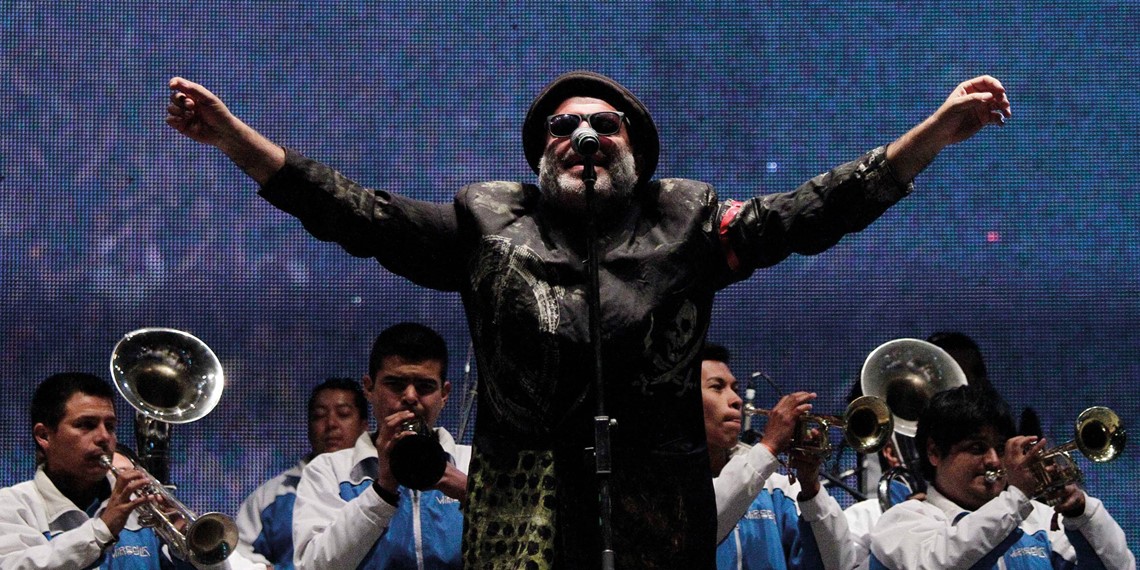

Macha at Chile’s Frontera Festival (David Cortes Serey)

Though the cueca is Chile’s national dance, it is fair to say that cumbia is not far behind it in terms of popularity. It’s a style regularly played at Chilean festivities and parties, though it has often been looked down upon due to its association with the working classes. “It’s music of the lower classes, of the poor,” Macha says. Chico Trujillo take inspiration from this Chilean love of cumbia, but they offered something different right from the off. They mixed up the tempo, gave their horns a jumping two-tone makeover and injected it all with a raw, iconoclastic energy that cared little for commercialism or “the music industry.” They released their first album in 2001, which would later be reissued in Germany with the title Arriba Las Nalgas! (a rallying cry from the group during their live shows, it means ‘get your asses up’ or ‘get them moving’).

Their follow-up was recorded live in Berlin, a city that had become a spiritual home for the group. Astonishingly, they played for 40 consecutive nights in Café Zapata in the then-artist-occupied squat Kunsthaus Tacheles, then took a four-day break, and returned for another 14 nights. Discussing their relationship with the people of Berlin, Macha says: “It was a cultural shock, on both sides. I remember them saying that they didn’t understand anything that we were saying, but that it was impossible not to move or to dance.”

While Berlin showed that the group were destined to have universal appeal, they also caused a stir back home, where their take on cumbia heralded a movement known as ‘New Chilean Cumbia’ or ‘Chilean Cumbia Rock,’ with countless groups taking inspiration from Macha’s lead. “Here, in Chile, they have generated something very beautiful with the cumbia, these bands of youngsters playing it,” Macha says of his fellow cumbia groups. “They have recovered this fiesta that was half hidden. Also, this is a natural thing, because during the time of Pinochet it was difficult for a band to play cumbias.” Of all of the cumbia groups, the Chilean newspaper La Tercera has noted that Chico Trujillo are the only ones who have done it while ‘reconfirming the dance [cumbia] with new rallying calls’ and not giving in to ‘commercial’ pressures.

This year the group – which has expanded to 11 members, and that’s not to mention their frequent guest collaborators – released their latest album Mambo Mundial, and their ethos is still intact. If anything, with age they are adding even more fury to cumbia’s irresistible beat. The album starts off with an ebullient, hip-swaying cover of ‘Qué Me Coma el Tigre’, originally written by the Colombian Eugenio García but made famous by the Spanish singer Lola Flores, then veers towards hip-hop on ‘Teclitas y Niños’ before dialling back the years with a collaboration featuring Los Gaiteros de San Jacinto, one of the most notable groups playing cumbia in its indigenous flute-led form. Most exhilarating of all is their take on a song that has been a staple of their live set for some years, their original track ‘A Mi Negra’, with its rebel-rousing singalong chorus (‘¡Ohohohohohohoh, hey!’), which segues into the popular 1950s Italian song ‘O Sarracino’. It’s the perfect document of why the group have become such an in-demand live band, full of rhythm and hooks, and with the power to get the crowd moving, despite the language barrier.

(photo: Florent Brique)

Just as Chico Trujillo had begun as an offshoot of La Floripondio, Chico Trujillo in turn gave birth to a new group. In shows they started giving space to a style of song known as canción cebolla (onion songs, ie they’ll make you cry) and which included ballads, boleros and other romantic songs. This section of the show was called the bloque depresivo (the sad part) and it soon became so popular with audiences and the band that, in 2010, it became a group itself, Macha y el Bloque Depresivo. All acoustic, and often featuring some of Chile’s most revered folk musicians, the group are infusing energy and passion into songs of the Latin singer-songwriter canon that many thought were past their best. In typical Chico Trujillo fashion, they did not find stardom the easy way. Their circuitous route involved a live recording of a concert in Paris’ Théâtre de la Ville in 2012, which was uploaded to YouTube. This show was soon bootlegged and found its way to homes across Chile, where an audience for this nostalgic but passionate music was clearly present – the clip currently has over eight million views. An actual album would not arrive until 2018 when Barbès Records released their self-titled debut.

The album contains their takes on songs such as ‘La Nave del Olvido’, recorded by Mexican crooner José José in 1970; the Peruvian waltz ‘Cada Domingo a las Doce’; and, most bizarrely, the schmaltzy 1978 Italian pop ballad ‘Sóló Tú’, originally recorded by Matia Bazar, but given a swooning accordion-led makeover by the group. Discussing why he started singing this music, Macha says: “I’ve always liked these songs that you hear at 4am when the bar is closing. I like to sing these extreme feelings and for a long time I was curious to learn them.” As to why the project struck such a chord, he’s matter of fact: “The people like this music because they know the songs from certain points of their life.”

As if all this activity wasn’t enough, Macha also recently started a fourth project, Las Cabezas Rojas, which takes Chilean folk (ie the Andean-influenced world of Los Jaivas and Huara) on a highly experimental journey through space rock and beyond. With just a few tracks released so far, an album will undoubtedly drop soon, though DIY in spirit as ever, there’s no knowing exactly when.

Through all of these groups it’s hard not to think of Macha as an innovator, a musician putting himself on the line constantly to push music that is either experimental or out-of-fashion. Yet, when pushed on his success and the connections he has made with audiences worldwide, he cuts me off: “Look, what is important to me is to make music. I have two bands where I make everything original [La Floripondio and Las Cabezas Rojas] and where I move in the experimental realm and two that move around popular music [El Bloque Depresivo and Chico Trujillo], which I love. I move [with] them and we play, having the opportunity to participate with other musicians and also learning about genres. I’m neither a master in cumbia nor a master in bolero, what I’m doing in this shit is to play, and besides that, to learn.”

But did he ever think that these bands would be so successful? “For me, can you imagine? It’s a dream, it’s magnificent. I get to travel, learn, play different styles of music, and I can count on a team of friends that help me, and I have the luck that people like it.” And the bewildering thing is it seems like he’s only just getting into his stride, with more currently unannounced projects to come and new collaborators that are helping him push the limits of what can be done in the studio (their live shows have been peerless for some time). Surrounded by great musicians, with classics old and new ready to be belted out, there are few better places to be than with Macha and co.

This article originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of Songlines. Never miss an issue – subscribe today!