Friday, August 16, 2019

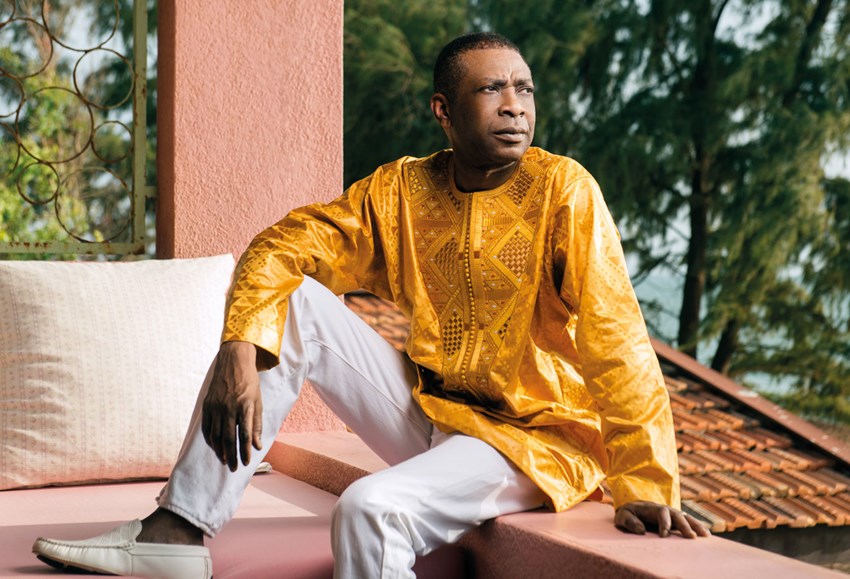

Youssou N’Dour interview: “Even today music can carry a message and change people’s lives”

Senegal has recently seen the long-anticipated opening of a museum dedicated to black civilisations. One of its chief supporters is Youssou N’Dour whose latest album, History, reflects on the past and acknowledges the next generation of artists. Jenny Cathcart reports

“There is no such thing as a minor griot,” Nicholas Cissé, the Senegalese architect and filmmaker, has said, commenting on Youssou N’Dour’s griot heritage. “All griots have inherited the same gifts of singing, playing instruments or talking. Their feats of memory are remarkable, the power of their words awesome. Each generation sings and speaks and plays and the words accumulate until the day when a plethora of words falls on one griot who receives the ultimate gift and becomes a megastar called Youssou N’Dour.”

Youssou has always been clear about his mission as an artist: “We the griots were once the troubadours, entertainers, keepers of history and chief advisers to the Mande kings, guardians of a culture which we have been at great pains to preserve. We have remained quite traditional until the very last minute before opening out to the world. I am a thoroughly modern griot, but I know that even today music can carry a message and change people’s lives.”

His latest album, History, seems to mark a moment when Youssou pauses to look back at his achievements and friendships, and, in the company of a new generation of artists, considers the future. A long-time advocate of African unity, Youssou’s album comes during a pivotal period in the development of Africa.

Youssou N'Dour (Photo: Youri Lenquette)

Back in 1984 at the outset of his career, Youssou wrote ‘Africa,’ a dreamily impressionistic meditation on the plight of a continent once united, carved up by colonialism, then free but splintered. ‘New Africa,’ a song which touched Barack Obama when he visited Dakar in 2013, calls for a meeting of minds, the elimination of borders, self-reliance, the sharing of ideas, responsible leadership and respect for exceptional Africans like the Senegalese scientist and philosopher, Cheikh Anta Diop, Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, or South African anti-apartheid activist and martyr Steven Biko.

Nelson Mandela, who was the subject of an early album, is for Youssou: “A great man, a role model and father to all Africans. No one gave so much of himself in order to construct a better world. When after almost half a century spent fighting for freedom and justice he willingly stepped down from office it was like the cherry on the cake and I said to myself, he is the greatest.”

Youssou described his 2016 album Africa Rekk (Africa Now) as a cry of hope, a message for everyone and especially for Africa’s young people, who need to take responsibility for their continent and work peacefully and resolutely towards sustained success in every domain.

Throughout his vast repertoire of over 500 songs, the Grammy award-winning artist, recipient of an honorary doctorate in music from Yale University and winner of various global prizes, has singled out African men and women as role models. Many, like Birima, the subject of one of the songs on the new album, resisted occupation and oppression. Birima Ngoné Latyr Fall, King of Cayor (1855-1859) was known for his dignity, courage and discretion. An efficient administrator, he refused to collaborate with the French colonisers and died in 1860 – poisoned, it was said, on the orders of Faidherbe, governor of Senegal. Youssou’s original recording of ‘Birima’ is one of the most impressive in his songbook. Performing it in April 1992 in the Léopold Sédar Senghor stadium in Dakar in front of 100,000 ecstatic young people and in the presence of president Abdou Diouf, Youssou seemed even more popular than the head of state, his showcase song virtually becoming a national anthem.

Now the richest musician in Africa, Youssou is a successful businessman who owns a media empire in Senegal. Having lived in Dakar all his life he has his finger on the pulse of public opinion. He stood as a presidential candidate in 2012 in order, he said, to defend democracy (he objected to the incumbent president Abdoulaye Wade’s attempts to change the constitution and remain in power for a third term). He is committed to growing prosperity and opportunity across a continent where 60% of the population are under 25. He campaigned alongside Bono and Bob Geldof in the Make Poverty History campaign and met president Bush in the White House to seek support for the fight against malaria in Africa. In 2001, following the attack on the Twin Towers by Islamist extremists, Youssou asked his New York record company Nonesuch to delay the release of his award-winning album Egypt precisely because he intended it to promote a greater understanding of the peaceful message of Islam.

At the same time as Africa is becoming, in the words of business magnate and philanthropist, George Soros, ‘one of the few bright spots on the gloomy global economic horizon,’ (Asia Asset Management, March, 2012), Youssou is aware of an equivalent surge in creativity in the arts, fashion, and music – notably Afrobeats – that is attracting international attention. Africa is revealing its 21st century face to the world.

Back in 1966 at the official opening of the first Festival of Black Arts, president of Senegal, poet, French academic and promoter of Négritude, Léopold Sédar Senghor pledged to create a museum to house black artefacts and archives from around the continent and beyond. When Youssou was minister of culture he authorised the building of the ultra modern Museum of Black Civilisations that was officially opened by president Macky Sall in December 2018.

The museum’s director, Hamady Bocoum, explains the importance of Senghor’s initiative: “While intellectuals from Africa and the diaspora had met in London, Paris or Rome, the 1966 festival brought them together for the first time on African soil.” Around 2,500 black artists, writers and musicians appeared at the festival which was followed up by FESTAC ‘77 in Lagos and the Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres in Dakar in 2010. Here the declared aim was to showcase the diversity and vitality of black music and its influences throughout the world. An exhibition entitled ‘Great Black Music,’ created by Marc Benaïche was displayed during the festival before being installed in 2014 at the Cité de la Musique in Paris. The exhibition is now back in Senegal and may well find a permanent place in the new museum or in the planned Maison des Archives in Senegal’s new city of Diamniadio, 30km from Dakar.

Since the 1960s, independent African states have been asking for the return of art objects taken by colonial powers who at the Berlin Conference in 1884-85 carved up the continent for themselves. These artefacts remain in Europe’s museums including the British Library and the British Museum in London. “Not until we complete the process of de-Berlinisation, can we Africans reach the next stage in our development,” says Bocoum, France alone holds 88,000 objects from sub Saharan Africa including 70,000 in the Quai Branly Jacques Chirac museum in Paris. A report entitled ‘The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics’ (sic) was commissioned by the French president, Emmanuel Macron and completed by Senegalese writer Felwine Sarr and French academic Bénédicte Savoy. Published in November 2018, it concluded that art is history and all Africans have a right to understand their cultural heritage.

Youssou is a friend of and ambassador for the new Museum of Black Civilisations. He was among those who lobbied for the return of African objects and the purchase of significant contemporary art works for the museum’s first collection. These include Le Grand Baobab by Haitian-born sculptor, Edouard Duval-Carrié, Non au Jihad à Timbuctu by Abdoulaye Konaté (Mali) and Le Laboratoire Déberlinisation by the Senegalese artist Mansour Cissé who lives in Berlin.

On History Youssou continues a musical trend he began with his previous album, Afrika Rekk, when he veered away from his trademark mbalax towards other black rhythms from rumba to reggae, salsa to soul, and collaborated with younger African artists including the Senegalese American superstar Akon, Congolese singer Fally Ipupa, Nigerian guitarist Femi Leye and his compatriot Spotless aka Augustine Uche. Spotless is again present as arranger on History along with Seinabo Sey, a Swede of Gambian origin, a star of the new Scandinavian electro-soul scene. Mohombi Moupondo, born to a Congolese father and Swedish mother brings his beguiling voice to the track ‘Hello’. In an intriguing throwback to Nigerian jùjú music Youssou sings along with the Nigerian singer, master drummer, and campaigner for civil rights in the US, the late Babatunde Olatunji (1927-2003). Both of Olatunji’s tracks were offered to Youssou by the artist’s nephew because he admires his music. Pianist Mike BGRZ, a French beatmaker of Beninese origin, co-composed ‘Confession’ and ‘Tell Me’ with Youssou. Matt Howe, a friend of Peter Gabriel, mixed the album in his studio in Qatar, varnishing it with a modern pop veneer.

Youssou N'Dour

On the track ‘Birima Remix’, Youssou and his guests address the topic of slavery, with Sey remembering men and women in chains before proudly proclaiming, ‘This one’s for my father and his father. It’s about where we come from, not what you run from.’ Youssou could have revisited any number of his songs about exemplary figures like Birima. ‘Miss’ profiles Aline Sitoe Diatta, a Diola princess who led a fierce resistance movement against Portuguese colonial domination, later protesting against the French colonisers and opposing the drafting of Senegalese foot soldiers known as ‘Tirailleurs Senegalais’ – 93,000 of whom served in Europe during both world wars. As for the future, to those young people who work hard, who pray and keep the faith, Youssou offers the promise of success in ‘My Child’.

Importantly, History begins with Youssou’s heartfelt tribute, cradled in gentle highlife cadences, to his long-time friend and collaborator Habib Faye, the youngest member of the Super Étoile de Dakar, bass and keyboard player, acoustic guitarist, arranger and jazz virtuoso who passed away aged 52 in April 2018. Youssou recalls Habib’s exceptional talent, his courage, his love for his family and for music. If in his 60th year Youssou has mellowed, his four octave voice, described by Peter Gabriel as ‘liquid velvet,’ remains as distinctive as ever. He allows himself the luxury of revisiting two of his earlier love songs, ‘Ay Coono La’ (the original featured Habib Faye on fretless bass) and ‘Salimata’ (remarkable for the late Issa Cissokho’s splendid solo saxophone) and then offers a new one, ‘Tell Me’, the tenderest and most telling to date. Of course Youssou cannot resist a joke so he turns to ‘Makoumba’, the streetwise ‘Boy Dakar’ and, in one of his fast taasu (griot rap) style scats, teases him about his lofty dreams and feckless ways.

Youssou has gained millions of fans around the world and now the time has come when young musicians who have been influenced and inspired by his voice, career and success are eager to touch his coattails. This is also the story of how Seinabo Sey and Spotless, Mike BGRZ and Mohombi gathered in Youssou’s penc (historically the place where people came to listen to the king through his spokesperson/griot). They brought him their ideas and he shared his advice and his experience with them and together they made music.

+

More Check out a selection of our favourite Youssou tracks on our playlist: www.bit.ly/songlinesspotify